You’ve heard the quote from FDR, “The only thing to fear is fear itself!” When it comes to anxiety, the only thing to avoid is avoidance itself because it makes anxiety grow, not diminish. To understand this, let’s take a look at exactly what anxiety is.

Anxiety is Normal

First, know that everyone experiences anxiety. It is a 100% normal part of the human emotional experience and can be a good thing as long as it doesn’t become extreme and interfere with your functioning. You ask, “How in the world can anxiety be a good thing?!” The answer is that it serves a function in our survival. For our primitive ancestors, anxiety sent messages such as “you’re about to be dinner,” so the primitive human could run, fight, or hide.

Today, our anxiety is not often telling us that particular message. Instead, it is telling us that we must pay attention to something in our environment and consider taking action. This might be studying harder for a test, preparing for a hard conversation with a loved one, or even running from a would-be mugger.

It should be obvious then that nobody can stop feeling anxiety altogether. That would be as impossible a task as eliminating our need to breathe. And why would you want to if it can help you? So let’s learn to live with and tolerate anxiety by understanding it and responding to it in healthier, adaptive, and non-debilitating ways!

Brain Basics & Anxiety

Let’s start with an understanding at the most basic level HOW the brain creates anxiety. Then we can fully understand the WHY behind our reactions and help learn ways to reduce anxiety effectively.

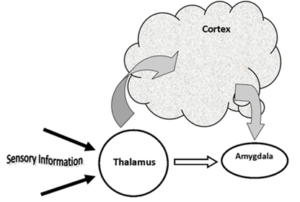

When we have any experience, our senses take in information and send it to the brain immediately. That information from our senses is routed to the thalamus. The thalamus sends that information to several different parts of the brain to be processed. There are two paths that lead to anxiety. One goes through the cortex (the thinking part of the brain). The other goes through the amygdala (the automatic alarm system). Everyone experiences anxiety through both pathways, though some may experience it more through one than the other. Our past experiences affect how we process the information.

Thinking Errors Cause Anxiety

The cortex, the thinking part of the brain, responds more slowly than the amygdala. Even so, it still requires less than a second to evaluate and fully understand the situation we find ourselves in. It accesses a great deal of stored information and memories to use in interpreting what is experienced.

Sometimes the stored information points to no danger and we can begin to calm the amygdala’s alarm response down. Other times the cortex agrees that we are in danger and need that stress response to continue to keep us safe. Sometimes it gets it wrong and misinterprets the situation altogether and creates anxiety-producing thoughts.

Where Do Interpretations Come From?

Many people believe that events cause you to feel a certain emotion: something happens and you have no choice but to feel a certain way. But an event cannot be the source of an emotion, because the same event leads to different emotions in different people.

Instead, what determines your emotional reaction is the interpretation that your cortex makes of the event. In many situations, what you think about the event determines how you feel. One interpretation leads to one emotion, while a different interpretation would lead to a different emotion.

Our cortex creates our reality to protect us from danger and keep us alive based in part on learned experiences. But the cortex can also create thoughts and images without any perceptions. In essence, it fills in the gaps, so that we aren’t completely dependent on perceptual pathways. The brain can perceive danger in the absence of our senses. To demonstrate, notice that your brain will fill in the missing lines in the image below so that you “see” the white triangle.

Remember that anxiety serves a function, and the cortex will initiate anxiety when it is appropriate to be paying attention and responding to something difficult, hurtful, or dangerous. But sometimes it creates anxiety unnecessarily. If we can change these thoughts and images whose interpretations “scare” the amygdala needlessly, we can better manage the anxious response and reduce overall anxiety.

Using Your Cortex to Reduce Anxiety

Situations in which you feel anxiety are opportunities to examine the interpretations that your cortex is creating in each situation. If you can identify the thoughts and worries that lead to your anxious feelings, you can work on changing those thoughts and worries.

Changing your thoughts is not easy. But, if you identify the interpretation that leads to your anxiety, you can question and dispute this interpretation. Then you can replace it with a less-anxiety-provoking interpretation.

When you change what you think about the event,

you change your emotional reactions.

Sounds simple, but it’s more difficult than it sounds.

- To change interpretations means you cannot avoid the anxiety created by these thoughts and instead must challenge them.

- You must be able to think.

- And to think, you must be able to tolerate the physical sensations of anxiety created in the amygdala, which means you must train your amygdala to not get activated as frequently.

Get to Know the Amygdala

You can respond to a threatening situation before you think because of the way your brain is wired. For example, imagine you are walking your dog in the woods at dusk and see something out of the corner of your eye that is curvy and thin on the ground. You jump back immediately thinking, “snake!” But when you look more closely, you see it’s just tree roots.

The immediate stress response, upon which the anxiety response is based, is triggered by the amygdala in the brain. The amygdala receives information very quickly and can initiate a quick response… which helps keep us alive. Think of it as a smoke alarm- it gets your attention and calls you to action.

We experience the amygdala response physically. Heart rate increases, pupils widen, and it causes us to jump back rapidly in response to stress. It is also wired to be able to quickly release adrenaline, so we feel jittery and ready for action. It can respond in error, of course, but it seems to operate on the idea that it is safer to respond in error than to take the risk of delaying a protective response.

So, the amygdala is responsible for very high anxiety experiences. This includes things such as shaking/bouncing legs, racing thoughts, losing focus, shallow breathing, and a pounding heart. We become focused on what is perceived as a danger so we can be ready to get out of it (fight/flight/freeze) before it’s too late.

Pairings

The amygdala isn’t programmed from birth to automatically react with anxiety and fear. Instead, it learns to react to certain events, objects, or sensations with these responses as it associates these with negative events. These events get stored in the amygdala as something that needs an anxious or fearful response in order to avoid danger in the future. This is a pairing.

Negative Events

Negative events are experiences that automatically cause some type of negative emotional reaction. They are unpleasant occurrences to which most people would have a negative emotional reaction (such as discomfort, pain, embarrassment, irritation, etc.). For example, to a child this could be a spanking or scolding from an adult; to a teen, it could be being called on in class when the homework was not completed; and to an adult, it can be getting injured at the gym or fired from your job.

Triggers

We hear people say they are “triggered” a lot these days, so let’s look at what that means. A trigger is a sensation, object, or event that does not lead to any specific emotional reaction by itself. It is originally neutral- just a regular sensation, object, or event. Triggers only come to produce fear responses when they are paired with negative events. (The trigger may or may not have caused the negative event.) Once paired, triggers can be sights, sounds, smells, tastes, or situations that make the person feel distressed, fearful, anxious, or uneasy when experienced. Often, the person begins to avoid not only the negative event but the trigger also.

Emotional Responses Are Learned

When a trigger is paired with a negative event, the amygdala creates a memory that connects an emotional response to the originally neutral trigger. This memory changes how the amygdala responds to this trigger in the future, even when that trigger is presented by itself. Whenever the person experiences the trigger, it elicits a fear reaction. They then experience anxiety because the fear reaction has been paired with the trigger- a learned response solely due to the negative event pairing.

These emotional memories can be both created and recalled by the amygdala outside of our conscious awareness. You may not be aware that something is a trigger until the learned fear/anxiety response happens when it is encountered again. Over time, you likely will start avoiding the triggers in order to avoid the negative emotional responses (fear, unease, discomfort, panic, etc.).

The amygdala’s activation can be seen as the driver of all anxiety disorders as it underlies and motivates anxious behaviors such as worrying, compulsions, addictions, and avoidance. It is not likely to forget the learned associations because its function is to keep us alive, so it will keep producing the anxiety response for years unless it is changed through repeated, new experiences so it can learn and create a new pairing.

Anxiety and Avoidance

Anxiety is defined by avoidance. Every time you avoid an anxiety-producing situation, your anxiety will be even worse the next time around. The brain sees it like this: “When I avoid this situation, I feel better. I guess I should try to avoid it next time too.” That relief only serves to reinforce your desire to avoid the situation. If you’ve ever heard the phrase, “What you resist persists,” you understand why avoidance is so detrimental!

Why avoidance behaviors magnify anxiety and stress:

- By avoiding, you are simply asking to repeat the situation and experience the anxiety over and over again.

- Avoidance behaviors don’t solve the problem and are less effective than more proactive strategies that could potentially minimize stress in the future.

- Avoidance can be frustrating to others; habitually using avoidance strategies can create conflict in relationships and minimize social support.

- Avoidance may allow problems to grow.

What Does Avoidance Look Like?

There’s the obvious, of course, where someone refuses to even put themselves near triggering situations. It can also be a host of other things. Procrastination, passive-aggressiveness, and rumination are examples of unhelpful avoidance coping. We may consciously or unconsciously use these to avoid tackling a tough issue or facing thoughts and feelings that are uncomfortable. Or we seek reassurance, refuse to discuss problems or face issues (denial), get angry, numb our emotions, or experience forgetfulness and racing thoughts (getting caught up in the content). We rationalize or isolate to avoid the negativity. Avoidance can look different from person to person and can depend on what is being avoided. Learn what you do to reinforce anxiety in the name of short-term relief. Begin by examining your urges when you feel those uncomfortable sensations you’re trying to avoid. What are YOU doing to avoid?

Here are some other examples:

- Avoiding taking actions that trigger painful memories from the past, such as not asking questions in class because it reminds you of a time you asked a question and the teacher embarrassed you.

- Trying to stay “under the radar,” trying not to be noticed lest someone see you struggling with anxiety and fear.

- Avoiding reality-testing or challenging your negative or anxious thoughts.

- People pleasing and self-depreciation to manage others’ reactions.

- Giving up on a goal, task, or project when an anxiety-provoking thought comes up such as, “This is hard” or “I’m not sure if I’m going to be able to do this.”

- Avoiding feelings of discomfort or uncertainty by seeking or forcing answers and taking control.

- Not starting a task if you don’t know how you’re going to finish it.

- Numbing or avoiding certain physical sensations that could create sensations akin to or trigger anxiety, such as getting the heart rate up through exercise, not engaging in intimate activities due to body image issues, overeaters may eat before feeling even slightly hungry, etc.

- Isolating or turning down social engagements due to self-worth issues, such as thinking, “I’m not the best. I’m not as good as other people.”

Changing the Response

Exposure and Response Prevention (aka ERP) is the only intervention proven to produce lasting change in amygdala activation.

Exposure in ERP refers to exposing yourself to the thoughts, images, objects, and situations that make you anxious or want to start “safety behaviors” (aka ways you avoid or stop feeling anxious). Response Prevention refers to making a choice to not do those compulsive safety behaviors once the anxiety has been triggered.

When someone exposes themselves to the source of their anxieties and nothing bad happens, the anxiety lessens. The person then feels more confident that they can handle the situation the next time. They learn to tolerate the anxious sensations and they think more clearly. The amygdala learns that these situations are not dangerous. They are not to be feared and are manageable, even if they are uncomfortable and intense.

This is the basic idea of exposure therapy:

stop avoiding and face your fears.

Building a tolerance of your anxious feelings and thoughts, accepting the uncertainty inherent in life, and bolstering self-confidence through ERP is the only way to get control of your anxiety and retake control over your life. So what’s stopping you?

Roswell location

paige@restorationcounselingatl.com, ext. 157

Paige provides a safe and comfortable atmosphere, where clients can explore the challenges they are facing. She also believes in addressing the individual’s entire personhood, assessing needs in all domains of life instead of focusing solely on mental health needs. Paige works with adults and teens around issues of depression, anxiety, mood disorders, relationship issues, trauma, PTSD, and life transitions.

Reference

AppliedBehaviorAnalysisEdu.org. (n.d.). What is graduated exposure? https://www.appliedbehavioranalysisedu.org/what-is-graduated-exposure/

Boyes, A. (May 5, 2013). Avoidance coping: Avoidance coping plays an important role in common psychological problems. Retrieved from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/in-practice/201305/avoidance-coping

Pittman, C. M. (2015). Rewiring your anxious brain: How to use the neuroscience of fear to end anxiety, panic, and worry. New Harbinger Publications.

Raypole, C. (2/25/19). How systematic desensitization can help you overcome fear. https://www.healthline.com/health/systematic-desensitization

Scott, E. (Sept 17, 2020. Avoidance coping and why it creates additional stress. Retrieved from: https://www.verywellmind.com/avoidance-coping-and-stress-4137836

TherapistAid.com. (n.d.). Treating anxiety with CBT. https://www.therapistaid.com/therapy-guide/cbt-for-anxiety

by

by